This is the 5th post in my Visualization with React series. Previous post: React components

The lifecycle functions

I’m not going to go into great details on this, but a talk on React without mentioning the lifecycle functions would not be complete.

React components come with several functions which are fired when certain events occur, such as when the component is first created (‘mounts’), when it’s updated or when it’s removed (‘unmounts’).

Pure functional components, which we’ve been mostly using, don’t have lifecycle functions.

But components with a state can have them.

Some examples of usage of those lifecycle functions include:

- Before the component is rendered, you can load data. that’s a job for ‘componentWillMount’.

- After a component is rendered, you can animate it, or add an event listener. Use ‘componentDidMount’.

- Prevent a component from rendering under certain circumstances, even if it receives new properties or its state changes. Use ‘shouldComponentUpdate’.

- After a component receives new props or new state, you can trigger another function before the component updates (‘componentWillUpdate’) or right after (‘componentDidUpdate’).

- When a component is going to be removed, you can do some cleanups, like deleting event listeners. Use ‘componentWillUnmount’.

Oftentimes, you can simply get by by using the default behavior of React components, which re-render only when they receive different properties or when their state changes. But it can be really convenient to have that extra degree of control.

Here is an example of using these lifecycle functions in context.

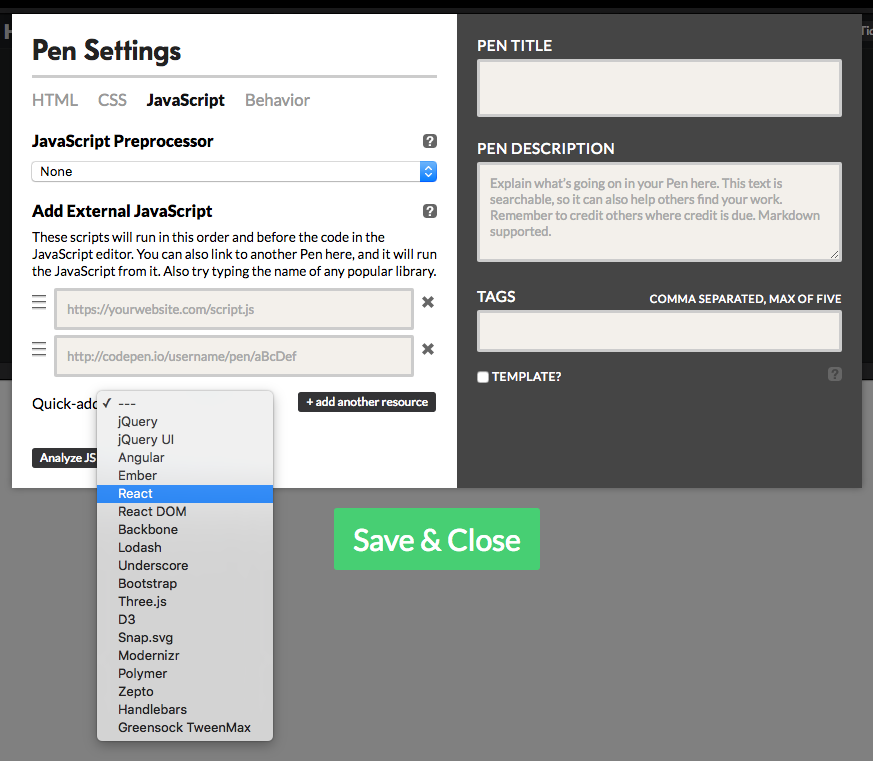

See the Pen lifecycle functions example by Jerome Cukier (@jckr) on CodePen.

What is going on there?

We’re adapting our earlier scatterplot example, only this time, we are not using pure functional components (which don’t have those lifecycle functions), but creating classes.

We’re going to have three classes: Chart, at the highest level; Scatterplot, a child of Chart; and Points.

Chart passes data to Scatterplot. What it passes depends on whether the button is clicked. That button changes the state of Chart (which causes a rerendering of the Scatterplot and the Point elements).

Chart also has a private variable that holds a message we can display on top. We can still use callback functions to change this variable, just like we change the state, but the difference between changing the state and changing a private variable is that changing a private variable doesn’t cause the children to re-render.

When we first create the scatterplot element, the componentDidMount function is called, and the message is changed to reflect that.

Then, each time we click the button, a different data property is passed to the Scatterplot element. Also, the componentDidUpdate method is triggered, which changes the message.

(changing the state of the parent from a componentDidUpdate method can cause an endless re-rendering loop, this is why I used private variables instead of the state, and there are ways to address this but for the sake of brevity this is the easiest way to deal with that problem).

Now, when a full dataset is passed to the Scatterplot element, many Point elements will be created. I’ve also added a lifecycle method to these Points: when they are first created, they receive a small animation. To that end, I have also used the componentDidMount method, but this time at the Point level.

Exit animations are also possible, but – full disclosure – they are less easy to implement in React than entry animations, or than in D3. So again in the interest of concision I’ll skip these for now.

React and D3

We just saw that with React, we can create a DOM element, then immediately after, call a function to do whatever we want, such as manipulating that element. That function would have access to all the properties and state of that React element.

So what prevents us from combining React and D3? Nothing!

We can create components that are, essentially, an SVG element, then use componentDidMount to perform D3 magic on that element.

Here’s an example:

See the Pen mixing react and d3 by Jerome Cukier (@jckr) on CodePen.

In that example, I have used a bona fide bl.ocks (https://bl.ocks.org/mbostock/7881887) and wrapped it inside a React component. So I can create one, or in the case of that example, several such elements by just passing properties. Those components can perfectly function as black boxes: we give them properties, they give us visualizations that correspond to these parameters. And it doesn’t have to be D3 – once a React element has been created, we can use componentDidMount to do all kinds of operations on it.

In the last 2 articles I will present actual data visualization web apps made with React.

In the next post, we’ll see how to set up a simple web app and we’ll create our first example app.